11 How data is stored

11.1 What this chapter is about

This chapter is about how data gets into the computer. Once we have collected our dataset how do we store it? Why should you care about how a computer counts and stores data as an economist? Knowing how a computer counts allows you to estimate the size of datasets and how to optimally store data.

Economists often work with datasets with millions (or billions) of observations and thousands of variables. Such a dataset can take hours or even days to open. Moreover, understanding how data is saved is important when the data looks different to what you expected. For example when the sentence “Thomas Müller plays for Bayern München” looks like “Thomas Müller plays for Bayern München”, what went wrong?

Intended learning outcomes

After reading this chapter you should be able to

- Use binary counting (base 2 counting)

- Explain how computers store information (What is a bit?)

- Explain what bits, bytes, kilobytes, megabytes and gigabytes are

- Explain what decoding and encoding are.

- Estimate the size of a dataset

- Use the tidy data principles

11.2 How computers work

1 or 0

More or less everything you do on a computer is based on binary numbers. Binary numbers are numbers that only can take two values. We often think of them as 0 or 1. But it could also be true or false, low or high and so on. When you are reading these chapters, reading a news story, playing a computer game or watching a movie, you are essentially looking at a very long list of zeros and ones, just like the list below. Your computer or mobile device is just transforming these values into interpretable content.

A very simplified description of how computers work is that they receive an electronic signal or they do not receive a signal. These two states correspond to the binary states, which we often call zero and one. Students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) created the video below to illustrate how computers work, where the binary signal is set by manual switches. You can watch it here:

Figure 11.1: How Computers Compute (Science Out Loud S2 Ep5). Source: MITK12Videos

From 0 and 1 to interpretable content.

How do we get from zeros and ones to letters, colors and movies? To understand how this works, we have to understand binary counting. You probably learned binary counting at some point, but we are all more used to decimal (or “base ten”) counting, where we use ten different symbols to count. The numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. Binary counting is not very complicated. In fact, the key difference is that we only use two symbols, 0 and 1, and it is thus a “base two” system. To understand how it works, let us briefly recap how the decimal counting you use every day works. Consider the number 123:

- The 1. number from the right denotes how many “\(10^0=1\)”s: 3

- The 2. number from the right denotes how many “\(10^1=10\)”s: 2

- The 3. number from the right denotes how many “\(10^2=100\)”s: 1

- The sum of the above is thus: \(3 \times 1+2\times 10+1\times 100\)

So when we say 123 we are essentially saying 1 times one hundred, two times ten, and three times one.

Note that every time we moved to the left we multiply the value of the number by ten. The rightmost number represents ones, moving one step to the left we get the tens, and one more gives the hundreds. If we had an even larger number, we could continue to thousands, ten-thousands etc. This is because it is a base 10 system. If we instead of multiplying by ten multiply by two, we have the base 2 system. The rightmost number again denotes the number of ones, and the second number from the left now denotes the number of twos (\(2\times 1\)), the third number the number of fours (\(2\times 2\)), the third number the number eights (\(2\times 4\)), and so on. Let us try to write the same number as above (123 in base 10) using base two:

- The 1. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^0=1\)”s=1

- The 2. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^1=2\)”s=1

- The 3. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^2=4\)”s=0

- The 4. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^3=8\)”s=1

- The 5. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^4=16\)”s=1

- The 6. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^5=32\)”s=1

- The 7. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^6=64\)”s=1

- The 8. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^7=128\)”s=0

- The sum of the above is thus: \(1 \times 1+1\times 2+0\times 4 +1\times 8 +1\times 16 +1\times 32 +1\times 64 +0\times 128.\)

Which is equivalent to the decimal above. So 123 in decimal numbers, expressed in terms of binary numbers is: 01111011. How did we figure out the combination that lead to 123? we started backwards and asked: How many 128s can be included? Zero. How many 64s can be included? And so on.

From signals to bits and bytes.

We can thus count to any number using just a binary signal, as long as we have enough signals. But why did I include eight signals above, when only seven were needed? Recall from above, that a computer counts by receiving signals. The signal is that either there is a signal or there is no signal. Such a signal is called a “bit”. We typically measure data sizes in terms of “bytes”. A byte simply corresponds to eight bits. The string of eight values above therefore easily converts into the language you are used to when talking about file sizes on a computer.

If you have a (very small) file that is “1kb” big it means that it contains 1024 bytes or \(1024\times 8= 8192 bits\). Such a file therefore contains 8192 zeros or ones and in principle we would be able to continue the list above to have 8192 rows and write a very large number:

- The 1. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^0=1\)” we have.

- The 2. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^1=2\)” we have.

- The 3. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^2=4\)” we have.

- \(\vdots\)

- The 8192. number from the right denotes how many “\(2^{8191}=..?\) (a very large number!) we have”

We wrote in “principle”, because this is not how the computer would save such a number. Take for example the number 128. Using just 1 byte, the computer could save this number as “01000000”. However, if you create a new empty file on your computer, you will discover, that this is not what happens. Instead it is likely that the file content will contain three bytes and look like the following:

00110001 00110010 00111000Let us try to translate this.

- The first byte is \(1 \times 1+0\times 2+0\times 4 +0\times 8 +1\times 16 +1\times 32 +0\times 64 +0\times 128=49\)

- The second byte is: \(0 \times 1+1\times 2+0\times 4 +0\times 8 +1\times 16 +1\times 32 +0\times 64 +0\times 128=50\) * The third and last byte is: \(0 \times 1+0\times 2+0\times 4 +1\times 8 +1\times 16 +1\times 32 +0\times 64 +0\times 128=56\)

So somehow 49, 50 and 56 translate into 128. Computers use a set of rules to translate the signals into letters, numbers or pictures. The set of rules is defined by the “encoding scheme”. The document created above was saved using the 128 encoding scheme. According to this scheme a 49 is translated to a 1, 50 to 2 and 56 to 8. We will return to the encoding schemes below, but let us first try to shed some more light on bits and bytes.

A never ending confusion 1000 or 1024?

If you ever bought a 1GB memory stick and checked the capacity on a computer, you might have discovered that the computer says the capacity is less than 1 GB. Why is that? Basically it is a confusion between decimal and binary counting. \(2^{10}=1024\) is very close to the number 1000, which we call “kilo”, \(2^{20}=1,048,576\) is close to 1,000,000 which we call “mega” and \(2^{30}=1,073,741,824\) is close to 1,000,000,000 which we call “giga”. If you say 1GB (1 gigabyte) you might therefore refer to 1,073,741,824 bytes or 1,000,000,000 bytes. Not all systems use the same aggregation (Linux/Unix systems may for example differ from Windows systems).

How fast is your Internet connection?

Another source of confusion when talking about bytes and bits is the “B” vs “b”. The former relates to bytes, the latter to bits. If we are talking about 1GB we mean 1 gigabyte. If we are talking 1Gb we are talking about 1”gigabit”. If you have an Internet connection with an advertised speed up to “50 Mbps” it means that it is able to receive up to 50 megabits per second. So remember that 1 byte is 8 bits, and 50Mbps therefore means that you should be able to download \(50/8=6.25\) megabytes per second.

To recap, after reading this section you should be able to: * Distinguish between decimal and binary counting. * Explain how a computer saves information in terms of sequences of binary signals.

11.3 Encoding

How encoding and decoding works

We now know that a computer stores information by means of binary signals. We can translate these signals into numbers, but it is not yet clear how to translate these signals into letters and symbols. To achieve this, computers use rules where a number is translated into a numerical value, a letter or a symbol. So the computer has a set of bytes: 00110001 00110010 00111000, in decimal terms this corresponds to 49, 50 and 56. The computer then looks up in a large table which says that: 49=1, 50=2, 56=126. So the list of bytes represents the number 128. going from 49, 50 and 56 to 128 is called decoding, which is what the computer does when you open a document. When you save a document the computer encodes the content from letters and symbols to first a decimal number (using the big table) and then to sequences of bytes.

To get terms straight: We say that we encode something when we convert something into a coded form, so if you take something in readable form and convert it into code, you are encoding it. You are decoding a piece of code if you are converting the code into readable form. }

Where does the big table come from?

So where is the big table that the computer uses to look up numbers? One of the most famous tables, i.e. set of rules to translate the number derived from a sequence of bits is the “American Standard Code for Information Interchange” also known as ASCII. ASCII contains a list of 128 numbers and the corresponding symbol. The full list is available here, but a small excerpt of the full list is reported here:

| Decimal number | Symbol |

|---|---|

| 48 | 0 |

| 49 | 1 |

| 50 | 2 |

| 51 | 3 |

| … | … |

| 65 | A |

| 66 | B |

| 67 | C |

So a file with the binary code “01000001” would show an “A” if the ASCII encoding scheme was applied. This happens as follows:

- Step 1: The computer receives eight signals, corresponding to a byte: .

- Step 2: This translates into the decimal number \(1 \times 1+0\times 2+0\times 4 +0\times 8 +0\times 16 +0\times 32 +1\times 64 +0\times 128=65\).

- Step 3: The computer looks in the ASCII codebook (Table @ref{tab:store2}) and realizes that if it sees a number binary number that corresponds to the decimal number 65 it should print the symbol A.

When you are writing a text document the reverse happens. You enter an A, the computer looks up the table, notes that this corresponds to the decimal number 65 and converts it into a binary number and saves it as a string of signals.

The basic ASCII codebook contains 95 symbols that we can read and 28 instructions that we cannot directly read, such as whitespace, tab, backspace and so on. But because it only contains 128 symbols, which can be saved using seven bits, the first bit in a byte will always be zero using the ASCII encoding. This is basically a waste of resources.

There are many codebooks. What a mess!

This all sounds straightforward. Unfortunately 128 symbols aren’t sufficient to show all symbols of all languages in the world. This creates the issue where “Thomas Müller plays for Bayern München” looks like “Thomas Müller plays for Bayern München”. There are many encoding schemes, and if a file on the computer is encoded using one scheme, but the computer decodes the binary codes using a different scheme, the symbols will look odd.

Encoding and decoding: What you should know and do?

Should you know the code tables? Certainly not. You should know that they exist and that there are many versions of them. It is also worth knowing that the most popular encoding schemes are ASCII and UTF-8. We will return to that.

If things look fine: do not worry. Luckily, in most cases you do not need to worry about the encoding and decoding schemes. Most files contain some instructions to the computer on what scheme to use.

When you navigate on websites, they will typically report the coding scheme to the browser (i.e. Google chrome, Firefox, Safari, Internet Explorer), and the browser makes the correct interpretation. Even if websites do not include information about which scheme to use to translate information, browsers are typically able to guess the encoding scheme quite well.

What you need to know is that if something looks wrong, it is most likely due to the encoding and decoding gone wrong. You should also know that the encoding can affect the file size, we will return to that later.

Let us consider an example where things have gone wrong: The pictures below show screenshots from the online version of the New York Times. It is the same frontpage, but in the first version, some text is garbled. For example the headline “Trump Offers a ‘Steel Barrier,’ but Democrats Are Unmoved” should be “Trump Offers a ‘Steel Barrier,’ but Democrats Are Unmoved”, as illustrated by the lower picture. What happened?

Figure 11.2: Screenshot from the New York Times website on January 7 2019.Left: Western (Windows 1252) encoding. Right: Unicode UTF-8 encoding.

What went wrong? I instructed the browser that the document it was showing was encoded using the “Western (Windows1252)” encoding scheme, but if you look at the source code of the website, you will find the element:

which instructs the browser to use the UTF-8 encoding scheme, which is the scheme used in the lower picture. So what went wrong is simply that we decoded using the wrong “coding scheme”.

Garbled websites are rarely a real issue, but here are some examples where encoding errors are problematic

-

Encoding issues in data

Imagine that you would like to investigate the average income across German cities. You have a large dataset, with a variable stating individual income and another variable stating “city”. You realize that the variable city has several values representing the same city. For the city München, you observe the values “München” and “Munich”, so to get the average for München you compute the average across all individuals with the city being either “München” or “Munich”. This is all fine and good. But if there is an encoding error, some observations might have the value “München”, which you do not include in your average. Your average is therefore wrong.

Encoding issues in scripts and codes. In a recent update of the popular statistical software Stata, the encoding support was changed. Version 14 of Stata of the software was the first version to fully support unicode UTF-8 encoding. This means that if you open Stata files created in version 12 or 13 in version 14, they will look garbled and instructions might not work.

The unicode encoding scheme

While ASCII used to be the most popular scheme, the unicode schemes are by far the most popular schemes today. The full unicode scheme consists of a table of 1,114,112 code points (or symbols). We call them code points, because the table is somewhat more complex than for the ASCII. Instead of providing a mapping between a binary code and a symbol, there is a mapping between a binary code and a code point, and a mapping between the code point and the symbol. These details are not important, and in fact the unicode code point 65 corresponds to the symbol “A”. Does that sound familiar? It should, because there is a 1:1 mapping from ASCII to UTF-8 unicode encoding, and 65 is the decimal number for the binary sequence representing A. So if a document was saved using ASCII encoding, but you instruct the computer to use UTF-8 encoding, you should not worry. You can think of ASCII as a subset of UTF-8

11.3.0.1 UTF-8, UTF-16, UTF-32

But how does UTF-8 relate to unicode? Unicode is the full set of code-points, while UTF-8 is a specific encoding scheme. There is also UTF-32 which uses 32 bits. 32 bits per symbol gives a lot of flexibility, but it will often take up a lot of space. UTF-8 is a flexible encoding scheme, because it uses the number of bytes necessary to show the information. Another encoding format is UTF-16, which is also flexible in length, but in contrast to UTF-8 it uses two bytes as a minimum (UTF-8 uses one byte). Documents saved using UTF-16 encoding will therefore typically be larger than documents saved with UTF-8 encoding. As the example shows, these differences can be substantial (almost twice the size), without being visible to the reader. So the encoding scheme is important because it determines whether the information is read correctly, and because affects the file size. In the next subsection, we will talk more about file sizes.

If encoding and decoding go wrong, what can you do?

If you discover an encoding and decoding scheme, there are a number of options to sort out the issue.

- Instruct the software you are using to save the content to use a different encoding scheme.

- Instruct the software you are using to read the content to use a different decoding scheme.

- Manually correct the decoding errors in the software that you are using to read the data.

11.3.1 Encoding: What you shouldn’t do!

Let’s end this discussion on encoding with a small warning. If you open a document that is decoded using a different codebook than was used for encoding, there is usually no problem. You discover the error, you ignore it or you solve the problem as above.

However, what you should avoid doing is overwriting the encoding scheme. Consider the following example:

- Your friend writes a document and saves it using encoding scheme X.

- You open the document and your software assumes it is encoded using encoding scheme Y. You ignore that some symbols clearly are garbled, make some changes and save the document using encoding scheme Z.

- Another friend opens the dataset and everything looks like a mess.

In the example above, it would require a lot of work to sort out the mess. To see why, let’s consider what happened.

- In encoding scheme X an “ü” is saved as the decimal number 5: Binary code 00000101.

- You use scheme Y to decode 00000101, which gives an “ü”.

- You now decode the symbols using scheme Z, where the “ü” has the decimal number 7. So the binary code now becomes 00000111

- To get back to the original “ü” we would need to know that some symbols should first be decoded using scheme Z, then encoded using scheme X.

11.4 Estimating file size and memory use

Variable types

When we store data on the computer we often ignore how the computer stores the variable. However, when you store large datasets, this can become very important, as a dataset might take up more space than necessary, because the type of the format of the variable is not aligned to the content. The specific list of potential variable formats varies depending on how you save the data (i.e. what software you use to save the data), but as a minimum, you should know the following types:

-

Boolean

- A boolean variable can only contain two possible values. True or false (0 or 1). You could for example have saved a variable with the content "female" as a boolean variable, where "true" would correspond to the case where the observation represents a female individual, and false otherwise. - Minimum size requirement: 1 bit. -

Integer

- Integer variables contain only whole numbers in a pre-specified range. The range depends on the size of the variable, if the variable is a byte, it will typically allow you to save values in the range from -128 to +127. - Typical size requirement: 1 byte (8 bits) (for values -128 to 127). -

Floating point numbers

- Floating point variables can take almost any numerical value. However, in practice the range and the precision is limited. The limit depends on the space allocated to the variable, but unless you work with very large or small values or very precise values, you do not need to worry about this. - Typical size requirement: 8 bytes (64 bits). -

Characters

- Character values contain text, and can include all symbols that are defined in the applied encoding scheme. - Size requirement depends on encoding, 1 byte per character at least for UTF-8 encoded strings.

Note that I ranked the variable types above according to their approximate size rank. Boolean variables can be saved using only very little space, while characters and floating point variables require much more computer memory. The specific ranking depends on how the variables are saved. We will return to this issue in the next chapter.

What is important for now is that the variable format type is important. Imagine that you save the foot size as a boolean variable. In that case you will throw away a lot of information, because the foot size can then only take 2 values. On the other hand, if you save the variable “female” as a floating point variable you will waste a lot of resources, because it uses more space than actually required.

File size

We now know what we need to approximate the file size. Let us now try to estimate the size of a dataset. Our dataset contains 10 variables and 20 observations. If all these observations are stored as floating-point numbers, the approximate file size is:

\[\begin{align} 10\times20\times8&=1600\text{ bytes} \nonumber\\ &=1600/2^{10}=1.56 \text{KB}\nonumber \end{align}\]

In most programs the data will be stored the in the RAM of the computer you are working on. 1.56 KB is not an issue in terms of RAM capacity for any modern computer.

But let’s consider another dataset, a dataset covering 6 million individuals over 30 years and 250 variables:

\[\begin{align} 6,000,000\times 30 \times250 \times8&=360,000,000,000\text{ bytes} \nonumber\\ &=360,000,000,000/2^{20}= 343,323 \text{MB}\nonumber\\ &=360,000,000,000/2^{30}= 335 \text{GB}\nonumber \end{align}\]

Our normal computers will not be able to handle this dataset in the RAM and loading this data will cause problems. Such datasets are not uncommon. If you are working with administrative data on an individual level, you often have sample sizes like that.

So what could we do? First, we should try to split the dataset up in smaller elements: fewer years and/or fewer variables. Second, we should try to save variables more efficiently. Do all 250 variables need floating point precision? How big would this dataset be, if all variables were saved as integers? Recall that an integer usually takes up one byte. The floating point precision number is thus eight times larger, and the same observations and variables saved as integers would then take up \(335/8\approx 42\)GB.

What happens if we use the wrong variable format?

So what if we converted our large dataset from floating point variables to integers and some of the variables actually included values that were floating points? Well it depends on the software you use to convert the variables, but the most likely outcome is that the value will be saved as “missing” if it is not covered by the used format.

Estimates are estimates

You will probably discover, that the file size estimates using the approach presented here tends to underestimate the actual file size. The main reason for this is that files include some “overhead”. The overhead might include information on the encoding type, but also information on the file format, which the software that reads the file uses.

11.5 The tidy data principles

Ideally we would like all raw datasets to be alike. As the R scientist Hadley Wickham puts it: “Like families, tidy datasets are all alike but every messy dataset is messy in its own way”27 Hadley Wickham28.

Why would we like all datasets to be alike? Having a standardized way of tidying data allows us to apply methods on various datasets, without bothering about the data structure. Imagine that you first created a very nice graph using one dataset. You would now like to create the same graph using a different dataset. Ideally, you would not have to change anything but the data source. This requires that the two datasets are organized in the same way.

To achieve a standardized way of storing datasets, a set of principles for “tidy data” have been set up:

- Each variable forms a column.

- Each observation forms a row.

- Each type of observational unit forms a table.

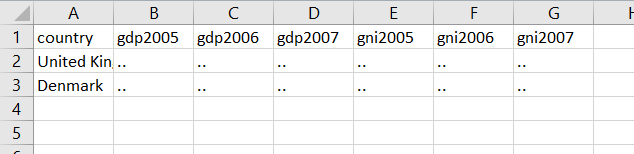

Figure 11.3 shows an example of a messy dataset. Why is it messy? Let’s first note the variables in this dataset:

- GDP

- Country

- GNI

- Year

This dataset has four variables, but the dataframe in Figure 11.3 has seven columns. That clearly violates the first criteria above: the number of columns should be the same as the number of variables.

Figure 11.3: A messy dataset.

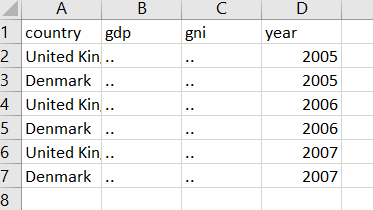

Let’s try to make it tidy. We tidy it by first creating new variables corresponding to those we listed above. The column Country already existed, but GDP, GNI and Year are created by separating the existing columns. The tidy version of this dataset is shown in Figure 11.3.

Figure 11.4: A tidy dataset.

Most statistical software (for example Excel and R) are designed for tidy datasets. You will see this in Excel when you create Pivot tables and in R when you create charts with ggplot.

29 also provides the following list of the most common issues with data:

- Column headers are values, not variable names.

- Multiple variables are stored in one column.

- Variables are stored in both rows and columns.

- Multiple types of observational units are stored in the same table.

- A single observational unit is stored in multiple tables.